its paid sponsors, whose products you need!

“Stay ‘unreasonable.’ If you

don’t like the solutions [available to you], come up with your

own.”

Dan Webre

The Martialist does not

constitute legal advice. It is for ENTERTAINMENT

PURPOSES ONLY.

Copyright © 2003-2004 Phil Elmore, all rights

reserved.

Stick to Sword to Knife, Part 2

By Phil

Elmore

WARNING!

Sticks, swords, and knives are

inherently dangerous. Do not carry illegal weapons and do not attempt

to use a weapon for self-defense if you are not trained in its use.

The Martialist cannot be construed as legal advice. The staff of

this magazine cannot be held responsible for any misuse of or errors made

with weaponry.

Those basic stickfighting angles translate

directly (with a few minor tweaks) to the use of the sword. I’m not

talking about Japanese Kendo or Iaido, nor am I referring to Highlander

pseudo-katana fencing. For best results, you want a

cut-and-thrust-capable sword. You don’t want one that’s too long,

either. A Japanese wakizashi would do, I suppose, as will a

machete (though its utility for thrusting is limited at best). For these

pictures I’ve used the CAS Iberia Banshee sword, which is a cutting sword

based on the Burmese “Da.” (If at all possible, you want a one-handed

sword. Two-handed techniques follow the same basic pattern of angles,

with the modifications necessary for occupying the formerly free hand, but the

live hand obviously cannot be used to check.)

As you can see from these pictures, the basic

angles are exactly the same. There is, perhaps, a little more “English”

on the strikes to take advantage of the cutting power of the blade as it

slices its way through the angles, but that comes naturally in slashing at

your target.

TRANSLATING BASIC ANGLES TO THE SWORD

|

ANGLE 01: DIAGONAL RIGHT The basic angle one strike is a diagonal cut across the This strike includes all logical variations on this diagonal, |

|

|

ANGLE 02: DIAGONAL LEFT Angle two is the backhand return of angle one, traveling diagonally This strike includes all logical variations on this diagonal, |

|

|

ANGLE 03: HORIZONTAL RIGHT Regardless of the level at which this strike travels from your right The target is the some portion of the opponent’s side, rather than |

|

|

ANGLE 04: HORIZONTAL LEFT Regardless of the level at which this strike travels from your left The target is the some portion of the opponent’s side, rather than

|

|

|

ANGLE 05: STRAIGHT THRUST Regardless of the angle at which the tip of the sword hits the Thrusts can be performed at any angle and as |

|

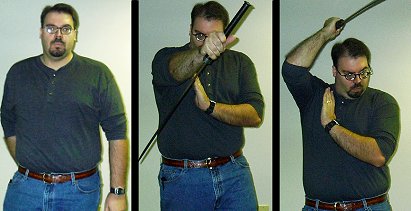

READY POSITIONS WITH THE SWORD

|

LOADED (LIVE HAND GUARD) Any cocked-and-ready position of this type is a “loaded” position. The |

|

|

FORWARD GUARD This sensible guard places the weapon between you and the opponent. |

|

|

LOW (ACROSS LOWER BODY) Those who favor backhand strikes may employ this low guard, in which |

|

BASIC BLOCK OR PARRY WITH THE SWORD

|

HIGH GUARD The high guard (sometimes called the “high wing”) is a deflection. |

|

|

ANGLE 01 BLOCK & CHECK Any angle one or angle three can be met with an angle one block and |

|

|

ANGLE 02 BLOCK & CHECK Any angle two or angle four can be met with an angle two block and |

|

Parries to deflect thrusts are performed with the sword in

the same way as for the stick, though the witik motion is slower for

the much heavier blade than it is for the stick. In training I’ve found

I tend to scoop when parrying with the blade (always using the flat,

not the edge) because the weight of the blade gives it momentum that imparts

an arc to the motion.

At close quarters, underhand techniques with the cutting

sword become an option. I don’t focus on these much except for sneaky

underhanded slashes across the opponent’s body.

The sword, held underhand and behind the body, can be

whipped forward

and out in a slashing motion across the opponent’s body.

THE KNIFE

Now that we’ve spent all that time inundating

you with pictures of me killing the photographer over and over again, let’s be

honest. You’re not likely to be carrying a rattan stick around with you

(though you might find an expedient weapon in your environment that can be

used like one). You’re also extremely unlikely to be toting a sword

unless you’ve watched

Highlander

a few too many times. You can, however, carry a tactical folding

knife very easily. The knife shown in these photos is a Cold Steel

“Night Force.”

I can’t carry a sword easily, but I have a knife.

Obviously, with something as small as a knife

compared to sticks or swords, the angles and the arcs they travel become much,

much smaller and tighter. Thrusts are not pronounced; they are

short, vicious pumping movements. While angled cuts to the attacker’s

limbs can be used to meet attacks, they do little in the way of blocking or

shielding. Instead, they are “defang the snake” cuts — slices to the

weapon-bearing limb intended to damage it.

Forward and backhand slashes are angle ones and angle

twos.

Horizontal cuts are angle threes and angle fours.

All motions are tight. Thrusts

are vicious and repetitive.

Reverse-grip knife fighting bears some

resemblance to the underhand sword techniques to which I referred earlier, but

the shorter weapon opens up many more options. The reverse-grip stab

downward becomes a very viable option in close quarters, for example.

There are hooking and trapping techniques that can be used with the reverse

grip, too.

Reverse-grip knife fighting is a topic unto itself.

As far as “ready positions” with the knife go, that’s up to

you. In general it’s better if your opponent doesn’t know you have a

knife until it’s too late for him to do anything about it. There are

exceptions, though, including drawing your knife while warding off an

approaching individual in the hope of deterring that person. (You can

never count on brandishing a knife to be a deterrent.) Your “knife

stance” will be a function of your training. (Don’t let me catch you

holding a knife over your head like some kind of fool.)

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

I don’t doubt that there are countless devotees of various

intricate systems out there thinking about the ways they approach these

weapons differently. I imagine they are enumerating various exceptions

to the general principles I’ve stated here, or writhing at the thought of

using a knife like a stick or a sword. The point, however, is that all

three of these weapons can be employed according to the general principles

they share.

There is no need to

complicate the issue further when the basics of one are the basics of another.