its paid sponsors, whose products you need!

“Stay ‘unreasonable.’ If you

don’t like the solutions [available to you], come up with your

own.”

Dan Webre

The Martialist does not

constitute legal advice. It is for ENTERTAINMENT

PURPOSES ONLY.

Copyright © 2003-2004 Phil Elmore, all rights

reserved.

Train the Stick to Learn the Blade?

By

Phil Elmore

One of those polarizing debates within the martial arts community revolves

around the question of training with sticks to learn knife and sword work.

Can one “train the stick to learn the blade?” Proponents of this idea

like the low cost and forgiving nature of sticks, as well as the benefits of

training the basics of multiple tools through one set of implements.

Critics assert that a stick is not a blade, does not handle in the same

way, and is not necessarily used identically.

The author, flanked by (tall) fellow

stick-to-blade

and Wing Chun students Al and “Evil” Scott.

Let’s take two roughly analogous weapons: the rattan stick and the

machete (or a similarly sized cut-and-thrust sword). Training with

sticks has obvious advantages over training with machetes. The sticks

cost less, are easily replaced, and present less potential for injury.

Depending

Depending

on to whom you speak, stick arts (Escrima, Arnis, whatever you want to call

them) are derived from blade arts driven underground by persecuting

conquerors. I am being deliberately vague because no two accounts I’ve

read (and no two sets of FMA argot) seem to agree completely.

Regardless, it’s true that you can do things with a stick that you cannot do

with a blade. Disarms that involve grabbing the “blade end” of the stick

or snaking in and around its length are good examples. It is theorized

that as the blade arts were practiced with sticks, they evolved and were

tailored to the specific nature of the cylindrical wooden weapons.

The way we hit with sticks and the way we strike with blades is intuitively

different. We tend, at least initially, to use more of a drawing,

slicing motion with a machete than we do with a stick. We hammer or

whack with the stick, cognizant of its blunt profile. The weapons also

weigh differently, meaning they handle and move with substantive differences.

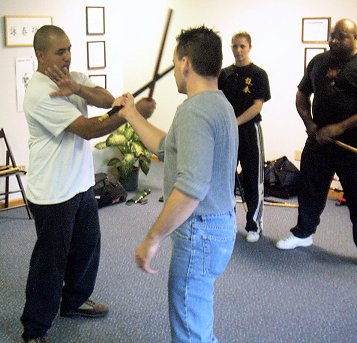

Sifu Eric Winfree (left) teaches a stick

disarm with student “Evil” Scott.

Critics of the “stick to blade” training theory will also point to edge

orientation or the lack thereof. Picture, for example, the Kendo

shinai. Students practicing sword techniques with this flexible and

cylindrical training “sword” may develop bad habits, flailing away to smack

their opponents with no real concept of their “sword’s” cutting edge.

The same problem can develop when using sticks to learn fighting with machetes

or short swords.

While there’s no denying these problems and differences exist, they can be

overcome through intent and through diligent training focused on that

intent. By remaining aware of the potential pitfalls, students of the

stick can make the transition to the blade and do so with confidence

in their methods.

Stick training at the Syracuse Wing Chun

Academy.

Before practicing any technique, the students must ask themselves:

“Can I use this technique with a blade and do so safely? If they believe

they can, they should test the technique carefully and under proper

supervision. If they cannot, their training should be biased against

that particular technique or theory. Sifu

Eric Winfree’s Kali students, for example, regularly train with sticks and

blades, applying their stick training to machetes as shown here.

As Sifu Winfree looks on, students practice

with sticks…

…And later make the transition to

machetes,

using the same techniques they’ve just practiced.

Diligent practice can retrain the way we strike with sticks,

replacing one’s intuitive hammering impulses with more goal-oriented

technique. A powerful hacking, slashing motion is extremely effective

with a rattan stick, imparting both snap and power. This becomes

devastating when the same technique is used with an edged weapon. With

proper snap in one’s technique, even a foam training weapon can become

quite powerful. Sifu Anthony Iglesias, armed with a foam “stick,” once

performed a witik a whipping wrist motion to strike my weapon hand.

He left a bruise. Picture doing that with wood and, better yet, with a

machete. The machete would not move as quickly, but it would move

quickly enough and do much worse damage.

Sifu Anthony Iglesias (right) makes a point

in class.

Differences

Differences

in weight do make a difference in the handling of weapons, but you must always

take this into account whenever taking up any implement. I have thick

hardwood fighting sticks that are easily as heavy as a light machete. They

handle differently than my rattan training sticks. That’s just how it

is: sticks of different materials and lengths weigh differently.

Knives and short swords weigh differently, too. I don’t believe any

serious student thinks he or she can master the blade arts while never picking

up a live weapon to do so. Training the stick to train the blade trains

the basics that these weapons platforms have in common.

Edge orientation can be trained with sticks.

Students learn to be conscious of a reference point on their hands: the

second knuckles of their fingers. They practice knowing that if their

knuckles are not properly oriented to the target, they are striking with the

“flat” of the “blade,” not the imagined edge.

There is no substitute for live blade cutting and practice to

achieve true proficiency with an edged weapon. Stick training, however,

will go a very long way towards achieving that goal. It will, in effect,

truncate the learning curve for the blade. Such training must be done

with a keen awareness of the differences across weapons platforms, of course,

and it must be done with an eye for identifying and eliminating bad habits.

Combined with judicious use of live weapons to complete the training, a “stick

to blade” curriculum helps students learn to use both categories of

weapons and to use them well.

While I understand the points made by critics of this training

theory, they must in turn understand that proponents of this idea do not

present it as the only way to learn the use of edged weapons or to

deploy those weapons in self-defense. It is, however, one sensible

way, because it capitalizes on training time and maximizes the utility of that

time. Learning one body of principles causes less confusion and makes

teaching easier and more efficient.

You can, in fact, train the stick

to learn the blade.