Well, it wouldn’t really be fair to say that sportfighting is the problem. More accurately, sportfighting is part of the problem and contributes to it. By “the problem,” I mean that of the countless training opportunities and curricula available, too many consider themselves the answer to the question, “How do I prepare myself for success in self-defense?” Too many of these self-proclaimed solutions are incomplete, misguided, or nearly-there. Among these is sportfighting. Sportfighting fails to prepare its adherents for self-defense for three reasons: failure of mindset, failure of strategy, and failure of tactics.

Author Phil Elmore understands the need to acquire skills like

groundfighting, but takes a dim view of those (not pictured)

who would hold up sportfighting as self-defense training.

Mindset

Tom Sotis once said, “It isn’t a fight until you want to stop, and have to continue.” The term “fight” denotes, simply, conflict: to struggle or compete. It has any number of connotations depending on context. The Martialist, however, is devoted to self-defense, rendering irrelevant any sporting or abstract meanings of “fight.” When we speak of fighting, therefore, we are speaking of nonconsensual physical combat in which one or more of the participants seeks to inflict deliberate grievous harm or death. The initiator of a fight seeks some objective (murder, injury, material gain, rape, etc.), while the other participant(s) seek to deny the initiator this goal (through self-defense).

Sport “fighting,” then, is not truly fighting at all in a self-defense context. While we can play semantic games with the terms, the point is that a substantive difference exists in the tenor and the character of self-defense compared to sportfighting.

Spoftfighters agree, mutually, to the conflict in which they engage. They come to that conflict understanding when, where, and under what conditions their “fight” will take place. They “fight” according to rules on a forgiving surface. They “fight” knowing that they face one and only one opponent. In all but the most rare contests, they “fight” knowing that their opponent shares the same goal: to win the contest. At any time they may choose to “take a dive,” to tap out, to throw in the towel. As intimidating and physically demanding as such contests may be, they are not fighting in a self-defense context. Such activities are physical competitions between consenting athletes, rather than matters of survival among combatants.

The result is a dichotomy between the combative mindset and the sportfighting mindset. The sportfighting mindset is symmetrical — it is a shared vision of what defines success in a sporting contest (no matter how brutal). The combative mindset is asymmetrical. The aggressor seeks to attain his goal, while the “defender” (the party who uses force preemptively or in retaliation) seeks simply to deny the aggressor this goal. The defender does not seek to “submit” or otherwise “defeat” his attacker primarily. The defender’s goal is merely to remove himself from the threatening condition, using whatever force and whichever methods most expediently accomplish this.

The problem of bringing a sportfighting mindset to the combative landscape of self-defense is that this leaves significant conceptual blind spots in the practitioner. Sportfighters speak often in terms that betray a glaring lack of realistic thought, from taking their opponent “to the canvas” to deliberately going to the ground with an attacker on unyielding or physically dangerous terrain. (A parking lot strewn with broken glass is no place to attempt a submission hold if you can help it.) The sportfighting mindset prompts its adherents to willingly dismiss (or simply fail to consider) important real-life self-defense factors.

These factors include the very real possibility of facing multiple attackers (the attackers choose the time and place, after all, and are more likely to stack the odds in their favor), which is the most glaring conceptual failure of sportfighting training (unless we’re going to consider tag team wrestling on television). Dealing with weapons is another extremely important factor. Environmental awareness is a third, given the exclusivity with which sportfighters focus on their opponents on a perfectly smooth and cushioned battleground.

To embrace the sportfighting training methodology, one gains demanding physical contact at the expense of considerations one must not ignore. Being able to KO or submit a single opponent at a prearranged time in a controlled environment according to specific guidelines is certainly training that is athletically beneficial. Conceptually, however, it is no more “fighting” than is a point sparring match. Both train useful physical attributes (the former much more so than the latter), but both completely ignore the mental and physical context in which self-defense takes place.

Strategy

Mindset leads us to strategy. This includes both training methodology and execution of one’s training.

Gabe Suarez, whose work I admire very much, wrote a brilliant article for Black Belt magazine in which he discussed the relevance of famed swordsman Miyamoto Musashi’s Book of Five Rings. (Gabe also wrote the best conceptual book on self-defense since Jeff Cooper’s Principles of Personal Defense. It’s called The Combative Perspective.) In the article, Gabe wrote something that will stick with me for a long time:

A lesson frequently learned early in a martial artist’s training is that those who are destined to win do so first by studying and then fighting. Those who are destined to lose tend to fight first and then study why they lost. Although no one can accurately predict the outcome of every battle and prepare specifically for it, you can certainly stack the deck in your favor.

Sound familiar? My former Wing Chun Kung Fu teacher thought so highly of the article that he chose to discuss it in class. Gabe Suarez understands fighting unfairly — and he understands the difference between fighting and sports.

The strategic failure of martial sports is, as I’ve said, driven by the symmetrical mindset of the athletes. Two opponents agreeing to “fight” and who are seeking a mutual goal are not defending themselves. If they were, they’d have driven past the gym, or jumped the ropes and run from the ring at the first opportunity. They’d have come to the canvas, if they could not avoid it, with knives and clubs and guns — and friends. They would not be concerned with performance as such. They would not have the luxuries of time limits and other restrictions. They would not “fight” in brief, comfortable clothing or soft shoes.

I’ve explained already that the sportfighting mindset, embedded as it is in contest and competition, ignores real-life factors that are wholly relevant to self-defense. Strategically, this manifests itself as an over-reliance on intentionally going to the ground, among other things. Groundfighting uses up your physical resources. It is extremely difficult to fight multiple opponents while engaged in trying to control a grounded individual (though if you’re going to manage it, you’d better get a copy of Coach Scott Sonnon’s Plural Assailant Engagements and start studying – hard). You are also in closer proximity to weapons like knives when engaged in grappling (standing or otherwise).

Groundfighting puts you in closer proximity to hidden weapons like knives.

Conceptually, sportfighters also overestimate the amount of control they’ll be able to apply in a self-defense scenario. While they proclaim loudly that they know their techniques work because they apply them on resisting opponents, they apply those techniques in controlled conditions that lack the countless random elements of real self-defense. Unless light fixtures are falling from the ceiling and spectators could enter the ring at any time — unless either of the “fighters” could have a gun or a knife and the bout takes place in the parking lot — there are few random factors in a sport match. Those random factors are too relevant to realistic self-defense to be dismissed.

A friend of mine once took down and subdued a man who attacked with a knife after my friend intervened in a domestic dispute in a parking lot. While my friend was bent over applying a picture-perfect joint lock, the aggressor’s girlfriend picked up the fallen knife… and stabbed my friend in the ass. A sportfighter who programs himself to fight to the choke, to the submission, to the tap-out, is programming himself for competition — not self-defense. Conceptually, he leaves himself vulnerable to attackers who fight unfairly and who do not recognize the parameters in which he trains.

Tactics

This brings us to tactics. Sportfighters often dismiss as “dirty tricks” or as gimmicks some of the most brutal techniques applied in realistic self-defense. Weak RBSD curricula in some schools help perpetuate this misconception. What sportfighters don’t realize is that the lethal techniques integral to combat systems and effective martial arts aren’t gimmicks, but mechanics integral to the systems in question.

Take, for example, eye attacks. I’ve seen sportfighters dismiss these as unworkable at worst and ineffective at best. In the first case, many claim that it is impossible to hit a small target like the eye in an adrenalized, resisting altercation. This is simply not the case. I’ve attended training in which students worked, under fatigue and pressure, to use their fingers to strike moving targets (beginning with a simple cardboard roll). Even under stress, it is possible to strike the eye and do permanent injury.

My Sigung at the time, John Crescione, taught a seminar in which he used this “high-tech” training tool for drilling the skills needed in accurate eyeball strikes.

I read a news account once concerning a brawl between two groups of strangers. It resulted in one man having his eye completely displaced from its socket. Anyone who claims a serious eye attack is no big deal has been dealt a low-power or glancing blow, not a committed attempt to damage the eye. An eye strike delivered with only partial intent is still not something one shrugs off easily. (I should know; it’s happened to me.) You can even punch someone with enough power to detach a retina. You can scratch a cornea without even trying to do so. It simply isn’t that difficult to damage your precious, irreplaceable, and vulnerable eyes. Now, care to find a training partner to help you practice full-power “alive” eye-strikes? Care to find a martial sport where they’re allowed?

The combatives chin jab — a palm strike up under the chin, sometimes combined with an eye rake back down — is potentially fatal and extremely damaging when done properly. An edge-of-hand blow to the throat is also potentially fatal. Neither of these techniques is so intricate or theoretical that it cannot be done under stress using gross motor skills. That’s why they were part of the WWII combatives curriculum as taught by luminaries like Col. Rex Applegate. You cannot, however, train these techniques on unprotected human beings you will kill them.

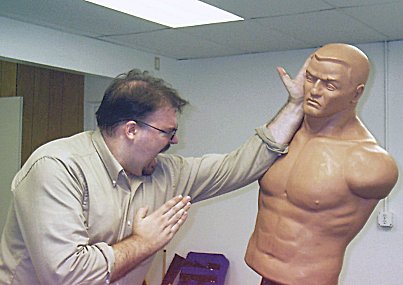

The Body Opponent Bag is a static training tool, but you couldn’t do this

to an unprotected human being without risking serious injury or death.

As a result, techniques integral to pragmatic self-defense can only be trained on human torso dummies and properly protected individuals. (I took a chop to the side of the neck once at extremely low power and almost passed out. At full force, it might have left me dead.) Sportfighters contend that the limitations of such training relegates it to the realm of theory, whereas what they do is tested and applied. This is spurious logic. Any gross motor movement can be replicated under stress. If it couldn’t, it wouldn’t be a gross motor movement. You must use a dummy or padded assailant to train fatal techniques unless you’re a sociopath or a street brawler. By the same token, an opponent fighting you to submission or KO isn’t trying to kill you.

Sportfighting is as much part theory as is RBSD or combat martial arts, simply because it lacks that element of lethality and opponents can quit any time they want. That is why training of any kind is training, not experience. It’s always part theory. The question we must then ask is, “Will my training prepare me for my goals, or does it miss the mark?”

Sportfighters do one thing very well. When they hit, they hit hard. Sporfighting that entails wrapped hands and gloves will give the practitioner a false sense of security (and probably lead to broken hands in real self-defense), but on the whole I won’t argue with this aspect of martial sports.

The last big problem I will identify is the fact that most sportfighting completely disregards weaponry. I said before that this was a conceptual blind spot. Tactically, It translates to both a lack of respect for the lethality of weapons and an ignorance of both their utility and their limitations. (One would expect weapons to be disregarded in sports, of course. Only a weapon art trained like a sport compensates for this shortcoming. Many varieties of FMA are trained with full intent and power, while others train using special equipment and gear. “Live steel dueling,” the Dog Bothers, and even the Society for Creative Anachronism all come to mind.)

Overall, the tactics of sportfighting are geared to the strategies and mindset of sports. This means that while some of them may apply to realistic self-defense, others do not.

Sport? RBSD? TMA? MMA?

One’s training methods need not be mutually exclusive. That is, I would encourage you to seek out training that covers all necessary aspects. Coach Scott Sonnon, whose conceptual approach to combat athleticism is second to none, describes in his Flow Fighting what combat systems and sport systems have to say about one another. Specifically, he describes the argument that undermines modern training:

Sport systems, say the combat systems adherents, are single, unarmed, and take place in a protected environment, whereas combat is plural, armed, and takes place in a hazardous environment. Sport systems adherents complain that often the techniques of combat systems are not proven in practical application, nor tested against resistance.

Both points of view are wrong, Coach Sonnon says, because the two camps are both right. Combat systems offer reality to sports — and sports offer competition, trial against an uncooperative opponent, to combat systems. The two should be combined and integrated to yield effective training for fighters.

“Alive” training with realistic levels of contact is very important.

Where I take issue with sportfighting adherents is when they start swaggering around holding up their sports as fighting. In the context of self-defense, a mutual contest is not a fight, and physical brawling — no matter how strenuous — is not self-defense. Sportfighting can provide very real benefits, especially if you perceive a lack of realistic contact in your training. Sportfighting is not, however, self-defense training. The goals, mindset, and strategies of self-defense differ from those of sports, leading to substantive differences in technique and training methodology.

Being able to drive a car makes it easier to learn to drive a tractor-trailer or a race car, but commuting to work is not training for trucking or racing. To say, “If you want to be a professional driver, you have to drive, so learn from drivers” is to confuse the goals of different driving activities.

I would no sooner fight an MMA athlete than a stevedore or a rugby player — because these are tough men who regularly engage in activities that make them strong and aggressive. (If you don’t think being a stevedore requires aggression, you haven’t done it.) Playing rugby, however, does not prepare me for self-defense primarily, any more than do MMA and wrestling.

Good self-defense training includes realistic contact, lethal technique, weapons training, multiple assailant training, scenario and mindset training, and a focus on the combative mindset. Sportfighting can be a valuable part of your self-defense curriculum, but it cannot replace it and it should not be your primary means of self-defense training.

If you want to learn to defend yourself, you must not lose sight of your goal or its nature. Sports ignore the tenor and character of that goal by definition, or they would not be sporting contests.

Nobody should know that better than sportfighters.