One of the first things my teacher Dave taught me was, “Stop being afraid of yourself.” His intent was to train out of me the hesitance that characterized much of my early training. I still remember the first time we engaged in the exercise, working outside one sunny Spring day. Dave told me to imagine that one of my feet was nailed to the ground. He was going to attack me. I was to defend myself, to counter-attack, without giving ground. I could move around the pivot point of my foot if I needed to, but I was not to let him force me back.

One of the first things my teacher Dave taught me was, “Stop being afraid of yourself.” His intent was to train out of me the hesitance that characterized much of my early training. I still remember the first time we engaged in the exercise, working outside one sunny Spring day. Dave told me to imagine that one of my feet was nailed to the ground. He was going to attack me. I was to defend myself, to counter-attack, without giving ground. I could move around the pivot point of my foot if I needed to, but I was not to let him force me back.

It was a daunting prospect at first. Dave is much smaller than me but possessed so much more skill that sparring him was very intimidating. Over time, though, it became much easier. I reached the point where I actually preferred sparring Dave, because I knew that I would learn something each time.

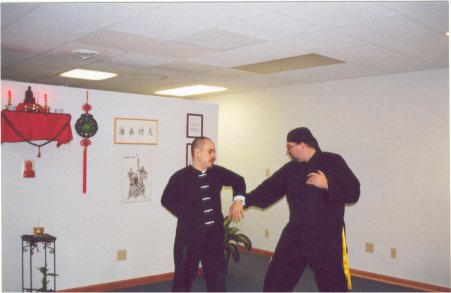

Early in my training with him, Dave and I engage in a

modification of Shanliang Li’s One-Hand Drill.

Interestingly enough, roughly one year after Dave became my instructor, different coworkers of mine told me, at different times, that I was “more assertive” or even “more aggressive.” They said at the time that the change was apparent “in the last year or so.”

Coincidentally, both of my teachers commented on the physical expression of this change when it occurred. While working one-on-one with Dave or with Anthony, my former Wing Chun Sifu, I repeatedly, subconsciously, and slowly backed each one of them across the room. The process was quite gradual. We would be training and suddenly discover that we were once again too close to the wall. Both Dave and Anthony had to prompt me to back up more than once to give them more room.

Dave found this almost amusing and told me that it made him proud. To back up your opponent, to dominate the room in a way that gives you more space in which to operate while denying this to others, is an extremely useful tendency to cultivate. I would like to think this habit is a natural outgrowth of becoming more confident in one’s skills as a martial artist, but it is entirely possible that it requires conscious thought to develop.

When you spar and when you train (where applicable and prudent), push yourself. Resist the temptation to give ground. You may have to back up at times to take advantage of the footwork of your style, but when you do, follow up by driving forward to keep the initiative.

Dominate every space you occupy.

In my half of one of the point-counterpoint-style editorials here at The Martialist, I wrote of one encounter with a street person after parking my car downtown:

In Wing Chun we are taught that a potential threat must not be allowed to close within striking distance of you. You must attack the opponent preemptively when he enters this range. When approached by someone whom you do not trust, we are taught, you must put up your hands and maintain a safe distance. As the panhandler approached, my first thought was that I must, at any cost, keep him outside that distance – or else I would have to strike him, as I did not want him approaching me.…

You see, every panhandler you meet IS a potential threat to your health and your well-being. Under no circumstances whatsoever should you allow a street person to approach you

…I pointed at him, bringing my rear hand up in a subtle approximation of the double Wu Sau guard that is the default hand position in Wing Chun Kung Fu.

“Step away,” I hissed.

Now, I’m not describing this because I think I’m cool or because I think I have the ability to put the Fear of Phil into random strangers. I was simply enraged and I spat at this beggar with a hostility I did not realize I possessed. I reacted instinctively – but my instincts were, in this case, developed by training that simply took over under stress. I was pleased that when I needed it, I did not have to think about it. That is the goal of training to defend yourself for real-life problems.

The basic “Hey, stop, I don’t want any trouble” position is a bladed (angled) posture in which the hands are up, staggered, palms open. This does indeed look almost identical to the double Wu Sau guard. The arms create distance and provide a protective barrier for your body (and, more specifically, your centerline). The body language is clear: Do not come any closer. The open palms are less aggressive than vertical hands in appearance, but open-hand blows can be delivered easily from either stance.

Maintaining space while deescalating if possible. Open-

hand blows can be delivered easily from this posture.

Wing Chun’s double Wu Sau (“Guarding Hand”) posture. It’s

the same stance with the hands turned vertically. The body

is more squared to the opponent, but the idea is the same.Use your body and your body language to maintain space for self-defense.From this hands-up, palms-open, bladed posture, you have the option to deliver physical strikes if you must defend yourself. You also may choose to transition to a weapon (thus escalating the force used in the scenario). The most common justification for making this transition would probably be facing multiple opponents, in which case a “force multiplier” could be seen as a rational necessity on your part as the defender. (I’m not a lawyer, so don’t take this as legal advice. It’s safe to say that if you use a weapon in a violent altercation, you’re going to have to answer for your actions in court.)

If you carry a knife or a firearm on your strong side – in your waistband, in your front pocket, or behind your strong-side hip – the transition is as simple as dropping the rear hand to index the weapon. Simply preparing to draw your weapon can be done relatively discreetly, too. Here I am maintaining space with my weak-side hand while indexing the tactical folder in my right front pocket. Provided you don’t slap yourself like a gunslinger going for his piece, this needn’t be perceived as provocative until the weapon is actually drawn.

Indexing a tactical folder in the pocket

while maintaining space and protecting

the body’s centerline.The postures shown here are merely starting points, of course. What you do from the decision to attack (or to make the transition to a weapon) is up to you and will depend on your individual training. At that point, all bets are off. What’s important to remember is that, if at all possible, you must keep potential opponents outside the distance at which they can reach you to do you harm.

In another article here at The Martialist, I spoke of maintaining space when asked for the time in public:

If you’re obviously wearing a watch, you have two choices when asked for the time. You can be rude and refuse to give it, or you can comply with the request. The problem is that when approached on the street by a stranger, there is a chance – not a great one, but a real one nonetheless – that someone who asks you for the time is trying to distract you in order to assault you. Think about it: when you look at your watch, you typically look down at your arm, making you an easy target.

If someone you don’t know comes up to you and asks you for the time, you can easily minimize your risk. Step back casually, away from the stranger, preferably blading your body as you do so. Raise your arm rather than lowering your head, keeping that arm well away from your body and between you and the other person. In this way you can read the time while keeping your guard up.

Practice doing this so it looks casual rather than confrontational. There’s no need to drop into your Daniel-san crane stance and fire off a flurry of snap kicks just to tell someone they’re late for an appointment.

Do this properly and you will see the similarities between it and the posture(s) already described. The rear hand could be relaxed, or it could be brought up casually to protect the centerline. Pretend to be scratching your chest or simply talking with your hands, if you must, but bring that rear hand up if needed.

Step back and raise your arm to read the time. This

puts that arm between you and the other person,

keeping your vision directed up and forward.These are simple concepts and nothing really new. It does not hurt, however, to be reminded of them.

Some of the armchair experts across the Internet accused me of overreacting, of “dropping into a Kung Fu stance” to deal with a relatively benign situation. In so doing, these critics betrayed their ignorance – because the basic hand positioning to maintain personal space is fairly universal.

I’ve seen the stance referred to as a “I don’t want any trouble” position, a “fence,” and a “de-escalation stance.” Whatever the terminology, the basic concept is the same. When you are approached by someone who represents a potential threat to your person – be he a panhandler, a drunken barfly, or an incongruously aggressive stranger demanding the time – you must keep that person outside striking distance to avoid making yourself a potential victim.

At The Martialist I have written more than once about the utility of hands-up ready stances for maintaining space. These are as much a modification of the double wu sao guard of Wing Chun as they are the legacy of various Reality Based Self Defense and combatives instructors. The point of any “fence” or “de-escalation stance,” as of any other hands-up guard or warding posture, is to place the arms between you and a potential threat. This creates a physical barrier while asserting personal space boundaries.

Since I started advocating this method for dealing with being accosted, I’ve seen three major criticisms of hands-up ready stances. These criticisms raise issues worth addressing.

Hands-Up Stances Are Too Hostile

Many critics see placing your hands up in front of your body to be very aggressive – body language that can escalate an altercation because it appears threatening. While it’s true that assuming a double wu sao or flaring your fingers in tiger claws might look like the prelude to a duel, the appropriate posture for maintaining space is much less hostile. With the hands up, palms out, combined with appropriate verbalization (“Whoa, there, friend, nobody wants any trouble, let’s not crowd each other…”) the combative nature of the stance is mitigated.

Of course, any time you put your hands up, you are being combative to a point. You’re asserting your personal space and you’re essentially demanding that this be respected. Getting your hands up will always be more aggressive than passively allowing someone to encroach on your space. Yes, when you do this you run the risk of escalating an encounter, but that is the risk you run whenever you resist the will, the demands, or the approach of another person. That is what we train to do – to resist the use of force or the threat of force against us.

There will be those critics who say you should be ready to defend yourself from any position and with appropriate maneuvering of your body. Well, of course you should do this. Given the luxury of preparing for a potential threat you have identified, however, why would you not get your hands up? If action beats reaction, the man in a hands-up ready stance will always have a slight edge over the man whose arms hang by his sides. Given the option, getting your hands up provides a better shield than does waiting to put those hands up after an attack is initiated. Hands-up stances also provide an important visual cue for maintaining personal space – a cue that just isn’t as forceful when trying to maintain space with your hands down or through body movement alone.

Hands-Up Stances Constrict Your Focus

Some critics complain that a “fence” stance inappropriately focuses you on one person, prompting you to ignore or neglect potential threats from elsewhere in your environment. While this is always a possibility if one is not mentally aware, it need not be a byproduct of such a stance. You don’t need to turn your brain off or stop scanning the area with your peripheral vision simply because your arms are raised.

Some critics complain that a “fence” stance inappropriately focuses you on one person, prompting you to ignore or neglect potential threats from elsewhere in your environment. While this is always a possibility if one is not mentally aware, it need not be a byproduct of such a stance. You don’t need to turn your brain off or stop scanning the area with your peripheral vision simply because your arms are raised.

Even when dealing with a multiple attacker scenario, the greatest threat is presented by the person closest to you. Of course you should focus on that person, at least initially. Just how many ninja are hiding in the neighboring shrubbery is not your foremost concern. You must deal with the more immediate threat.

Let’s be clear about this, however. We’re not talking about focusing on the immediate threat to exclusion. You must remain aware at all times, even when dealing with someone physically. (That’s one of the reasons you must deal with a physical attack quickly and ruthlessly – because the person attacking you might not be alone. “He may have friends” is one of those phrases my Wing Chun instructor uses a lot. His point is obvious. This does not, however, invalidate the utility of the hands-up ready stance.)

Hands-Up Stances Are Vulnerable to Grabs and Breaks

This is the complaint that always kind of irritates me because it speaks to mild ignorance on the part of the critics. I don’t mean, though, that they must be “ignorant” if they worry about having a finger broken or a hand grabbed, because these are valid concerns. Rather, they’re ignorant of the way such hands-up stances are used.

Hands-up stances are dynamic, not static. If you’re standing there like a potted plant with your arms extended and unmoving, you deserve to have your fingers broken. The whole point of placing your arms in front of your body is to facilitate action and reaction. The second your would-be attacker gets close enough to grab you, you should be doing something (in my Wing Chun school, the catch phrase is, “He’s too close, get him!”). If he reaches for your hand or arm, that hand or arm should be moving, countering, hitting, or whatever you’re inclined to do. It shouldn’t be just hanging there.

When I first started Wing Chun and applied the double wu sao guard in a sparring session with another teacher (who is not a Wing Chun practitioner), he grabbed my wrists and applied a crossing joint lock. I was ignorant of how to apply what I’d just learned at that early stage. I let him get too close and I left my arms there rigidly in position without shifting my stance.

Get Your Hands Up

A hands-up ready stance is a dynamic, fluid means of maintaining personal space while creating a physical barrier that improves your chances of defending against an assault. It is assertive, though it can be assertive without appearing actively hostile. It is not the magic solution to all self-defense scenarios.

Such postures are useful tools that, when applied with proper awareness and mobility, increase the odds in your favor.

Get your hands up and maintain space.

interesting…i have no idea of your skill level in real life but what ive just read makes perfect sense tactically. i came across this while just watching a bunch of street fight videos on youtube and was wondering what i could do legally to defend myself if i needed to in a public situation. obviously, anything goes on the street and you have no idea who you may be facing but it seems that most people on the street are relatively untrained. ive trained Muay Thai for about two years now and have sparred a good amount in that time, so i think id would do fine against most untrained people but the concepts you relate about personal space and “dominating every space you occupy” has really struck a chord within me. it is something i hope to remember and use the next time i spar in the gym.

THIS DOES NOT SOUND LIKE THE EDUCATED, ‘WIMPY’, MAN I AM. But it’s come down to this: I am homeless, and defenseless, against invasion of my personal space by other homeless, or catching a baseball bat to the skull, or knife in the ribs. Religion says, ‘give him the shirt off your back, TOO, (rather than participate in violence). Well, when a person successfully cajoles something out of me (a smoke, a sandwich, pocket change), without consequences, I become a ‘next-timer’. Whenever the person needs something, he knows how to get it from me the ‘next time’. WTF! I am hopelessly conflicted. I was not raised to be a BULLY, or foolishly put myself in harm’s way, neither be a con-artist, nor snitch.

(heavy sigh)