its paid sponsors, whose products you need!

| Home |

| Intro |

| Current Issue |

|

Mailing List |

| Store |

| Strength |

| Subscriber Content |

| ARCHIVES

|

| Martialism |

| Pacifism |

| Q & A |

| Cunning-Hammery |

| Advertise With Us |

| Submit An Article |

| Staff |

| Discussion Forum |

| Links |

“Stay ‘unreasonable.’ If you

don’t like the solutions [available to you], come up with your

own.”

Dan Webre

The Martialist does not

constitute legal advice. It is for ENTERTAINMENT

PURPOSES ONLY.

Copyright © 2003-2004 Phil Elmore, all rights

reserved.

Attack Proof

A Book Review by Phil Elmore

John Perkins’

Attack Proof is a

remarkably good book that didn’t really teach me anything.

Before I get myself into trouble, let me explain. I

actively study two martial arts:

Wing Chun and

Shanliang Li. The former is an

infighting style characterized by centerline awareness, touch-go reflexes,

efficient striking, and the refusal to fight

force with force. The latter is a highly meditative art that relies

primarily on open-hand strikes and, despite its somewhat mystical outlook, is

also viciously practical in use against an opponent. Both arts contain

components of military combatives. I strive

to integrate these with the application of both.

The resulting combat style is a flowing, ruthless, and fast

expression of sound martial principles one that is sensitive to the

“energy” of an opponent’s movements and attacks and that permits me to work

around those attacks to quickly (or preemptively) counter them. It is a

style that relies on structure, not muscle alone, for the delivery of power.

It is also characterized by good balance and a flexible, adaptable approach

that relies on principles rather than rote techniques.

If this sounds a lot like the contents of Attack Proof,

the book made the same impression on you that it did on me. When I first

purchased the text, I did so specifically because (at first glance) its

contents seemed curiously similar to the ideas my Shanliang Li teacher was

trying to impart to me. As I read the text, I spent a lot of time

nodding approvingly. Very little the book contained was material I had

not seen before, but this was the first book I’d found that distilled most of

what I was learning in a single source.

This is not to say that the book is perfect. Too much

time is spent telling the reader how very unique and different is Attack Proof, some of the content is a bit melodramatic in tone, and some of the

street-smart advice offered in the Awareness chapter is of debatable merit or

relatively unoriginal. Perkins and his co-authors also advocate looking

“terrified” to put an assailant at ease, which one could argue only encourages

the attacker.

One of Attack Proof‘s tenets is avoiding

confrontation at all costs. The “pacifism of the warrior” is a concept I

cannot accept, for I believe there are some principles and some people for

which and for whom one must stand up in the face of disrespect, intimidation,

and non-physical offense. There’s no arguing that avoiding physical

confrontation is the path of least resistance where survival is concerned, but

I don’t believe in survival at any cost. Some things are worth

the risk of injury or death. This is, however, simply my personal

conviction.

Leafing through Attack Proof in the book store might

lead the reader to conclude that this is a mystical, Tai Chi-style text that

relies heavily on the energy-manipulation techniques of esoteric and internal

martial arts. This is primarily a misconception prompted by the numerous

photos illustrating what turn out to be drills, not fighting techniques.

While Perkins and his partners do spend some time discussing

chi, the fighting principles they advocate do not rely on “energy projection.”

Just as I view chi as a metaphor for the mechanics of body movement that I

learn in Wing Chun, the “energy” discussed in Attack Proof can be taken

as shorthand for the methods used in yielding to, redirecting, and countering

incoming force.

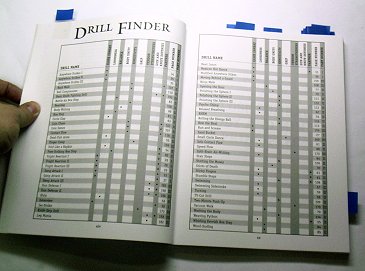

There are so many drills in Attack Proof that the

authors have included a two-page reference grid for locating them. The

level of participation the reader experiences is thus a matter of choice, as

each major topic is accompanied by suggestions for practice and attribute

development. Also sprinkled throughout the book are anecdotes from John

Perkins’ law enforcement career, margin notes emphasizing key points, and

helpful lists of tips for “Preventing Common Mistakes.” This is good

instructional design and enhances the clean, well-thought-out presentation of

the material.

After an introduction summarizing the book’s contents,

Perkins and his co-authors devote a chapter to Awareness (including the

street-smart guidelines to which I referred earlier, such as ATM safety rules

and strategies for avoiding pickpockets and muggers). The reader is

urged to develop “hostile awareness” in preparation for self-defense decision

making. Perkins also recommends the usual awareness texts: Gavin DeBecker’s The Gift of Fear and Sanford Strong’s Strong on Defense.

“Basic Strikes and Strategies” are covered in Chapter Two,

including a discussion of the “interview” phase of an imminent attack.

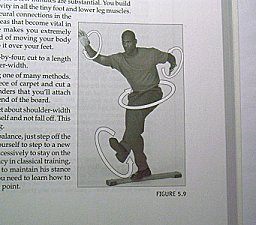

The “Jack Benny” stance, a common non-aggressive self-defense posture, is

illustrated and discussed. We are then introduced to basic combatives

strikes, including the chin jab, chops, spears, ridge hands, claws, rips,

tears, pinches, bites, head butts, and elbow strikes.

“Jack Benny” stance shown from the front.

The paragraph on head butts does not properly warn the

reader of the dangers of the technique. I would question the overall

conceptual efficiency of “pinches,” as well, but on the whole this is solid

information. The groin strike as magical off-button is debunked, low

knee strikes are mentioned, and low, non-telegraphic kicks are included in the

section. Closed-fist strikes are also mentioned, primarily to list their

dangers and shortcomings.

The need to deliver multiple strikes in rapid succession is

properly emphasized. “Guided Chaos” is used as a catch-all term for the

aggressive, flowing application of strikes (it is a portion of the title of

Part Two of the book, “Guided Chaos and Mind Principles”) used to overwhelm an

opponent.

In Chapter Three, “Looseness,” Perkins and company

explain how to remain relaxed, yield to a strike while preemptively or

reactively counterattacking, and “pocket” the body to avoid or absorb a blow.

The ensuing discussion is very similar to the application of touch reflexes

developed through Wing Chun’s chi sao practice

refusing to fight force with force and

flowing with or “running” around an attack to strike the attacker.

Chapter Four’s explanation of “body unity” veers into a

discussion of chi that will turn off advocates of pragmatic combatives, but it

is relatively brief. Fortunately, it also includes an anecdote from John

Perkins largely dismissing the “no-touch knockout” and “energy projection”

claims of some deluded martial artists. “…[A]s far as projecting a

shield of energy around the body,” Perkins writes, “…ask the claimant if he

would allow you to poke him in the eye. See if he can bounce your finger

off with pure energy.”

The chapters on balance and sensitivity that follow

reinforce the need to be rooted and the benefits of touch reflexes in

combat. Dropping the body as a source of power the key to both the combatives drop step and the

one-inch punch is mentioned. Different

types of “energy” are detailed. It is helpful to remember that this is

not a write-up of “the Force,” but an explanation of mechanics and kinetic

energy. The inclusion of this subject is not surprising given the link

to human kinetics

listed on the book’s copyright page.

In describing how to apply Attack Proof principles to

self-defense, the authors explain the characteristics of a good (and

“formless”) fighting stance, emphasize the need to

take your opponent’s space (the “forward drive” of combatives), and

examine “the body as a weapon.” It’s worth noting that Perkins advocates

striking quickly rather than trying to block a strike first, explaining that

the counter will happen incidentally. (Don’t confuse this with the

vulnerable striking-without-covering mentality of, say,

Hikuta, nor with the semantics of

SCARS though it is compatible with the simultaneous

blocking and striking of other arts.)

Chapter Eight explains “economy of movement.” This is

welcome material, for all of us should learn to move with purpose while

flowing in our application. A chapter on grabs and locks, with the

appropriate admonition to avoid groundfighting whenever possible, follows.

Counters to basic grabs and strategies for resisting a grappler are briefly

discussed as we move into Chapter Ten, “Ground Fighting and Weapon Defense.”

The basic weapons counters shown are sound, though the

paragraphs on multiple opponents might better have been expanded and moved to

a separate chapter, There are brief sections on sticks and canes, knife

defense, and keep-it-simple offense with a blade. Defending against

firearms at close ranged is also discussed.

The book closes with a brief review of “guided chaos,”

suggestions for developing a training regimen, and a glossary of terms.

One of the nicer features of the book is that it includes a topic index

something on which too many publishers skimp these days.

“‘Attacking the attacker’ is guided chaos in a nutshell,”

the authors write. “Using stealth energy, if you can slide through your

opponent’s attack while dropping, multihitting, yielding, and moving behind a

guard, your defense is actually an attack.”

While I am obviously pleased overall with the material

presented in Attack Proof, the name deserves comment. No

one, no matter how well-trained, no matter in what the individual studies, is

attack proof. The title is therefore disingenuous and smacks of

the type of marketing I hate most in the martial arts industry.

Once you get past this and the complaints I listed

earlier, you’ve got a surprisingly good book that distills many of the

principles and techniques I would advocate (and that I use and train myself).

No book is perfect and no single text can be all things to all people.

This book, though, gets quite a

bit right in a single volume.