Use by some branch of the military is often held up as the ultimate “street cred” for a martial art, combative system, or fighting technique. As anyone familiar with the process of selecting firearms for the military can tell you, however, the military is a bureaucracy first and foremost. Any weapon and any program related to a weapon owes as much to politics, budgets, influence peddling, and the conflict of individual agendas as it does to merit and efficacy. Ultimately, the only thing association with the military tells us about a product or curriculum is that the military has used it – for good or ill.

The combatives field manual used by the US Army as of this writing is FM 3-25.150, which supersedes previous Army programs. While it is encouraging to see our military working to update its programs, change for the sake of change serves no one but government contractors. I am sad to say that FM 3-25.150 is a dreadful manual, the curriculum in which is an unrealistic and impractical marriage of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) to battlefield combatives.

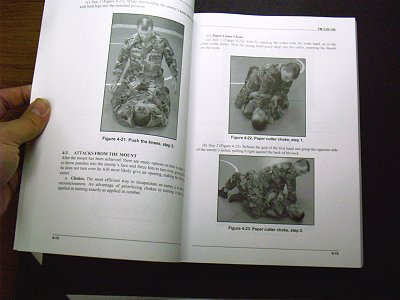

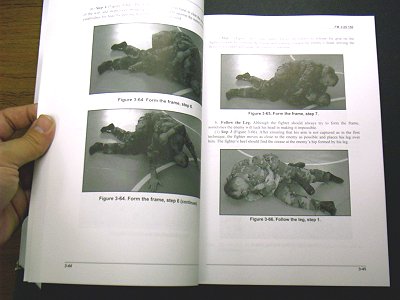

My reprint of the manual comes from Paladin Press, whose ad copy promises that it is an exact reproduction. The manual starts by defining combatives and the purpose of training in them before listing basic combative principles. These are mental calm, situational awareness, suppleness, base (what some call “rooting”), dominant body position, distance, physical balance, and leverage. Training safety is covered briefly, as are the responsibilities of trainers and a suggested program for unit instruction. The basic training program is allotted a mere 10 hours of available training time. The curriculum is built entirely around groundfighting — escaping and achieving the mount, passing hte guard, grappling for position, chokes, arm bars and sweeps, etc.

“Training should start with ground grappling, which is not only easier both to teach and to learn, but also provides a sound base for the more difficult standing techniques,” states the text. “A program should not begin with techniques that take a long time to master. The result would be almost uniform disillusionment with combatives in general.” Given the curriculum that follows, this statement would be amusing if this was some other nation’s manual.

After a section on creating training areas and obstacles, there is a section on stretching and an explanation of incremental training ideology. We then move to Chapter 3, which is titled “Basic Ground-Fighting Techniques.” Apart from a brief section on the bladed boxing-style “fighter’s stance,” the next 114 pages depict pairs of men in camouflage BDUs (one or both of whom are wearing sneakers…?) working through a seemingly endless succession of mounts, controls, guards, chokes, sweeps, and locks. Setting aside one paragraph on the need for dominant body position, there is no discussion of the dangers of groundfighting (particularly in the hazardous physical environment of a battlefield, where armed multiple opponents are virtually guaranteed and smooth gymnasium floors are few and far between). There are no strategies or techniques offered for avoiding going to the ground and no discussion of the increased danger of being knifed (or bayoneted, if you will) while grappling.

Chapter 5 is on takedowns and throws (Chapter 4 consists of advanced grappling) and complements Chapter 3. After a section on breakfalls, the clinch is illustrated. Basic takedowns and throws follow, which at least have more utility than ground grappling in a combative context. Headlocks with and without punches are covered, as are takedowns against walls, leg attacks, and lifts. The chapter concludes with brief segments on the leg sweep and rear attacks.

Finally, in Chapter 6, we get to strikes. The arm strikes are basically boxing methods — horizontal straight punches, hooks, uppercuts, and elbow strikes. There’s a paragraph on punching combinations and a short section on kicks. The leg techniques covered are limited to front and side kicks, plus shin kicks and knee strikes.

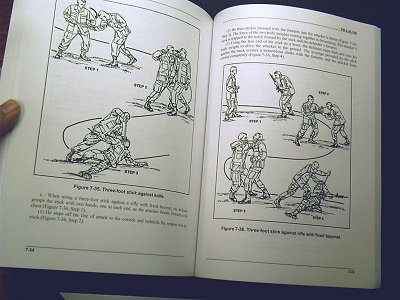

Before you know it we’re in Chapter 7 on handheld weapons. The Army divides the angles of attack into a fairly straightforward 9. We are then treated to a lengthy section on fixed bayonet fighting, followed by a few pages on knife fighting (which is adequate except for the too-crouched stance used, which makes a target of the fighter’s face). Three pages on the “three foot stick” and one on the “six foot pole” follow. As you can imagine, insufficient space is devoted to these weapons topics to do more than introduce them at the most rudimentary of levels.

Chapter 8, Standing Defense, is a bit better than the previous chapters. It includes practical counters for various offensive moves, though these moves will be much more common in off-base bars than on war-torn fields. There is also some knife defense material centered on blocking (or checking) and redirecting incoming thrusts and slashes — the value of which will vary wildly depending on context. The chapter ends with several sequences depicting defenses against bayonet-and-rifle attacks.

Chapter 9 is little more than two pages on group tactics. “Most hand-to-hand situations on the battlefield will involve several people,” the text finally admits. The viability of its 114 pages of groundfighting would seem shockingly dubious given this admission, but no attempt to reconcile battlefield reality with BJJ sportfighting is made. Appendices on situational training and conducting competitions complete the field manual. A glossary of 16 acronyms is also provided.

I haven’t exactly made an exhaustive study of military field manuals, but comparing this text to previous Army curricula reveals a disturbing contamination. Gone are the brutal, practical methods of Applegate and his WWII contemporaries, replaced by popular grappling sport methodology that turns the requirements of the battlefield on their collective ear. In an environment characterized — by definition — by armed, plural enemies often clad in body armor, committed grappling techniques are the least suited to the pragmatic needs of soldiers. Yet it is these methods that dominate the field manual, displacing appropriate techniques while flagrantly at odds with the context in which they are to be applied.

It’s hard not to call this the worst combatives manual yet produced by the Army. The popularity of BJJ has taken its toll on the curriculum, leaving me wondering how many years it will persist in military doctrine.

“Given modern equipment, complicated scenarios, and the split seconds available to make life and death decisions, soldiers must be armed with practical and workable solutions,” the text states. I agree completely.

It’s too bad much of FM3-25.150 is neither practical nor workable.

I used to lurk on James Sass’ Gutterfighting forum a few years ago, and I recall somebody claiming to be an Army combatives instructor defending this manual on the grounds that the program “helps build physical fitness and competitiveness, and soldiers never fight hand-to-hand anyway”. The discussion went on at some length, and you can probably imagine the reaction of guys like Cestari, Grasso, et al. to such schoolyard silliness. Just thought I’d mention this in case you didn’t remember it.