its paid sponsors, whose products you need!

| Home |

| Intro |

| Current Issue |

|

Mailing List |

| Store |

| Strength |

| Subscriber Content |

| ARCHIVES

|

| Martialism |

| Pacifism |

| Q & A |

| Cunning-Hammery |

| Advertise With Us |

| Submit An Article |

| Staff |

| Discussion Forum |

| Links |

“Stay ‘unreasonable.’ If you

don’t like the solutions [available to you], come up with your

own.”

Dan Webre

The Martialist does not

constitute legal advice. It is for ENTERTAINMENT

PURPOSES ONLY.

Copyright © 2003-2004 Phil Elmore, all rights

reserved.

Canadian Law and Self-Defence

A Book Review by Tony Manifold

WARNING! This article and

Ted Truscott’s book do not constitute legal advice. Neither Ted nor

reviewer Tony Manifold is a lawyer. The commentary contained herein is

for informational purposes only and cannot be construed as advocacy of a

specific course of action.

Canadian Law and Self Defence is, to my knowledge,

the only book that deals exclusively with Canadian law (in other words, the

Criminal Code of Canada and the case law that provides the framework for

interpreting those laws) and its relevance to self-defense. I am sure there

are legal books that deal with defending against assault charges, but

Canadian Law and Self-Defence is written for martial artists by a martial

artist. This is extremely helpful, as Ted has an intimate knowledge of how we

as martial artists (and, by extension, RBSD practitioners) may differ in the

situations we face and in our responses to those situations.

Ted Truscott is a Karate and self-defense

instructor based in Victoria, BC. He has decades of martial arts

experience. They dont call him “the fighting old man” for nothing. He teaches

Shorin-ji Ryu Karate primarily but has experience in Shotokan, Modern Arnis,

and Bagua Zhang Kung Fu. He also puts on F.A.S.T. Defense seminars (with the

help of his Bulletman, Joe Ferguson) and teaches

cane fighting for

seniors. He is not a practicing lawyer and has no law degree of which I am

aware. As such, he writes this book from the perspective of a martial

artist and private citizen. With that said, this book is very well researched

and contains numerous opinions from lawyers and judges.

The book is a little dry to read. It reads very much like a textbook, full of

references and quotes with quite a bit less of Teds writing than I would have

liked. However, being only 126 pages long, it is not long enough to wear on

you. It was an easy enough read and I got through it in only a couple of

hours. The only complaint I have is that I wasnt able to get a feel for Teds

writing style. This is a shame, because Ted is a colorful guy and it would be

nice for that to come through in his text.

The publishing job is a professional one. This

is no booklet stapled together, but a proper paperback textbook. The copy sent

to me by The Martialist‘s publisher is a recently updated edition.

The changes have been made to deal with some changes to the law since the book

was originally published in 1995.

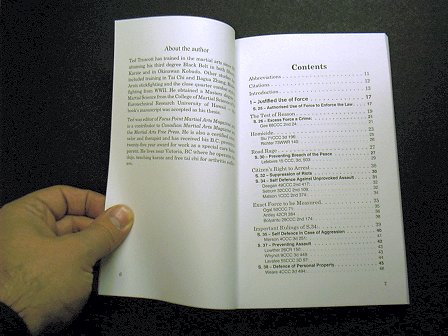

The book is broken into four parts. The first

three parts deal with the areas of the criminal code most relevant if you are

charged for defending yourself. They are Justified Use of Force, “Weapons

Offences, and Assaults. The fourth part of the book examines

how the courts deal with martial artists involved in violent scenarios. As I

said earlier, the book is written very much like a textbook. Ted details each

section of the Criminal Code, briefly explains what the sections mean, then

presents Appeals Court (a higher level court) cases in which judges have

interpreted the law in depth. This style makes it very easy to find whatever

you need. You simply look in the table of contents for the section of the

Criminal Code in which you are interested. Everything is right there for you.

Now, on to the meat of the issue. Where

does the law sit on the issue of defending yourself? I was surprised at some

of the cases in which self-defense was allowed as a defense. In many of

the cases listed, the accused was someone who brought an illegal weapon to an

illegal activity (prostitution, drugs, etc), used that illegal weapon to kill

someone who attacked him, and then successfully claimed self-defense. This

bodes well for us law-abiding citizens. One thing Canadian Law and Self-Defence

did for me was dispel the myth that the courts are out to get you and anything

but the most non-violent approach will get you jailed.

Another myth the book dispels is the idea that

you must measure the results of your response in the middle of combat.

Remember the Before and After Rule?

Canadian Law and Self-Defence gives the legal justification for such

thinking. Ted writes:

[D]ifferent situations will be judged differently and

[during] combat there is no need to stop to analyze precisely how much force

is now necessary for you to use. The courts seem to respect the so called “fog

of war” and will judge your response based on your perception of the event

when you first start to act physically.

In line with this thinking is the matter of

dealing with an armed attacker. The Appeals Court concluded that A person

defending himself against an upraised knife cannot be expected to weigh with

a nicety the exact nature of the force that he may use to preserve himself.

In other words, while you do not have carte blanche to kill anyone who

threatens you with a weapon, there is some latitude in what level of force will

be deemed justifiable.

On the issue of weapons, Ted counsels that

objects may be classed as weapons based on how they look. This means that the

super high speed 5 inch tactical knife is more likely to be judged a weapon,

whereas the 9 inch hunter may be classed as a tool. It surprised me that

we, as Canadians, have the right to arm ourselves

sort of. Edward Greenspan (a

lawyer of the Ontario Bar) was quoted saying, [Section 87, Possession of a

weapon for dangerous purposes] does not prohibit persons from arming

themselves

if the accused carries for self defence a weapon that is an

appropriate instrument with which to repel, in a lawful manner, the type of

attack reasonably apprehended and if the accused is competent [in its use].

Ted gives ample evidence that shows just how

important it is to been seen to make every effort not to fight. Under Canadian

law, if you consent to a fight there is no assault if you are then struck.

This means you must be very careful with your words and actions. If you imply

consent, you may lose your right to claim self-defense. As an interesting side

note, Ted includes a small section on duels.

The final part of the book deals with how

courts look on martial artists or anyone else deemed to be trained.” The cold

reality is that some judges assume that martial artists have the ability to

defeat their attackers without hurting them. This supports the notion that you

must be able to defend every action you take. Ted describes a civil suit against

a night club in which a patron was subjected to a lateral neck restraint by

a bouncer whilst being ejected from the club. The bouncer was Al Carty, an

accomplished and very experienced martial artist. In this case, Mr. Cartys

long martial arts background worked against him. It should be noted that Mr.

Carty did a very good job in using his background as a defense. He said, in

effect, that because of his background he knew what he was doing and could apply it

safely. In a criminal case he may well have been absolved of any wrongdoing,

but in a civil case the outcome is determined by a balance of probability and

is much easier to lose.

Overall, Canadian Law and Self-Defence is very informative and would

serve as a great reference for further training for any Canadian. I believe that if one owned

this book and had to face criminal charges, it would be a good text to give

to ones lawyer to keep him on the right track. The book is put together

well,

very organized, and contains information that is easy to find and digest. I would

recommend it to Canadian martial artists and self-defense practitioners who

wish to see where they stand in the eyes of the law.

I am definitely better off

for reading it.