its paid sponsors, whose products you need!

| Home |

| Intro |

| Current Issue |

|

Mailing List |

| Store |

| Strength |

| Subscriber Content |

| ARCHIVES

|

| Martialism |

| Pacifism |

| Q & A |

| Cunning-Hammery |

| Advertise With Us |

| Submit An Article |

| Staff |

| Discussion Forum |

| Links |

“Stay ‘unreasonable.’ If you

don’t like the solutions [available to you], come up with your

own.”

Dan Webre

The Martialist does not

constitute legal advice. It is for ENTERTAINMENT

PURPOSES ONLY.

Copyright © Phil Elmore, all rights

reserved.

Leaving Wing Chun

By Phil Elmore

Editor’s Note: This article is NOT at

attack on the Syracuse Wing Chun Academy, its student body, or its staff.

I have great respect for my former classmates and nothing but good memories

of those who taught me there. This article is about an introspective

process of discovery through which every student must go. It is

focused, as it should be, on the student in question me and not on the

school as such. Please keep this in mind as you read it.

In late 2004, I left the Syracuse Martial Arts Academy.

Then called the Syracuse Wing Chun Academy (SWCA), the school opened in 2002. I began my studies at the school when it opened and was, until the time of my departure, one of the Academy’s senior students. My rank level was three of an arbitrary ten, while the school’s most advanced student

at the time held a level four rank. The choice to leave the school was mine. No one suggested I should go, no one made me feel unwelcome, and I got along quite well with my fellow students and the school’s instructors, whom I considered good friends.

I trained at SWCA from October 2002 to

November 2004.

During my studies at SWCA, I tirelessly promoted the school. I was proud of where I trained and what I was studying. The virtual pages of

The Martialist contain much commentary that could be considered free

advertising for the school. I also performed small writing and editing tasks for

my teacher, free of charge. I wrote many articles at The Martialist praising Wing Chun as the effective infighting system I still believe it to be. I wrote often of my classes and of my fellow students.

Me (far right) with some of my former

SWCA classmates.

Wing Chun Kung Fu was very good to me. It improved my footwork, reinforced my cross-training, bolstered my understanding of how to take the initiative and close with an opponent, taught me to get off the attacking line and seek the opponent’s blind side when possible, gave me a better understanding of punching, refined what my Wing Chun Sifu once called “talented hands,” and generally galvanized years of inconsistent self-study. It made me a better martial artist, improved my confidence (in concert with my other training), helped make me more assertive in all areas of my life, and was, overall, an extremely positive experience. Through my Sifu’s eyes I got to view a much wider martial community. I watched with pride as the little school tripled in size after its first year, quickly and easily dominating the local martial arts scene.

I am not sure exactly when I started to hate it.

“Hate” is a strong word and perhaps not the most appropriate in this case. “It” is not Wing Chun Kung Fu, either, but training at the Syracuse Martial Arts Academy (then SWCA) specifically. There came a time when I genuinely disliked attending class. I don’t think I even realized this, at first. I forced myself to go, first automatically, then consciously.

Happier times, working my way through

the Wing Chun curriculum.

It took me a while to realize I was forcing myself to go. At first I

chalked it up to simple resistance to hard work a common enough problem for

any of us. I’d spent my first three months at the school wondering if I

should quit. I found the footwork complicated, the stances unnatural, the

chi sao pointless and boring. There were days it

seemed I just didn’t “get it,” when I felt limited by the constraints of the

style, when I longed to do things my way. I stuck with it, though

even managing to grit my teeth and remain after a rather disastrous test day in

which no one who tested for rank passed. I was glad that I stayed

after I started to understand and appreciate the training.

It was with this in mind that I kept at it, making myself go to Wing Chun

training even though I wanted nothing more than to skip it. “I guess I’ll

go to class tonight,” I would sigh to my wife. I did not want to be “a

quitter.” I did not want to give up on something that had been good for me

and which I’d truly loved.

My problems were only problems for me problems concerning what I

wanted in my training. When I first began training at SWCA, classes were a

diverse mixture of basics, self-defense techniques, weapons training, and even

sparring (though my instructor’s preference for “combat drills” quickly win out

and our brief flirtation with classroom sparring was over almost as quickly as

it began).

Over time, the curriculum and the class content evolved. My Sifu became

the disciple of another well-regarded teacher, one of the greats of the Wing

Chun world. His training changed, and with it, his students’

training. This was not good or bad; it was simply different, though

some of the diversity I enjoyed was replaced with renewed focus on strict

curriculum.

As my Sifu’s relationship with Sigung (my teacher’s teacher) went on, it was

announced that all testing would take place under Sigung either in New York

City, where Sigung was based, or during his periodic visits to SWCA. There

is precedent for this type of arrangement, but I was very much opposed to it;

I would not have enrolled with a school whose teachers told me at the outset

that I would have to travel in oder to test, or test only infrequently according

to another teacher’s schedule.

During this time perhaps throughout my training at the school my Sifu

became increasingly “old school” in his outlook. The training became more

traditional and as much about in-class physical conditioning as about training

in technique. I came to

the system expecting to learn self-defense while at least tolerating the

traditional aspects of the style. I was, however, starting to feel

increasingly out of place.

It became increasingly clear to me that the focus on old-school Gung Fu

while bound to produce capable, powerful practitioners wasn’t what I

wanted in a school. I’m a contemporary Westerner with modern attitudes and

a commercial outlook. While I can respect those of the “Old School,” I

don’t wish to be among them. I don’t wish to pay an instructor to

condition me physically; that’s not something on which I want to spend

class time when I can warm up and perform physical training on my own time (and

my own dollar). I don’t wish to learn self-defense incidentally while

learning a traditional style; I wish to learn a style or system in

order to engage in self-defense.

I spoke with my Sifu about my unhappiness with the training. He was

always happy to take time to discuss these things with me. He told me I

wasn’t training enough. He told me that if I spent more time with

Wing Chun, I would start to “get it” more and I wouldn’t be unhappy.

I thought about that for a long time. I couldn’t agree with Sifu’s

assessment, however. I “got” the training just fine and was learning

useful material whenever new techniques were covered. There was always a

learning curve during which I had to make my body perform maneuvers with which

it was not comfortable, but I always managed in time. No, it wasn’t that I

wasn’t “getting” my training it was that I no longer wanted it.

I loved that school. I used to go there and hang out when I wasn’t

training and had some free time, just to enjoy the company of my teachers and

classmates. I considered SWCA a second home, of sorts. To leave the

school to admit that I had become unhappy in my training was something I had

difficulty facing. I worried that my instructor would consider me an

outsider if I left. I worried that I would lose the friends I had there.

I worried that they’d all think less of me for choosing, of my own free will,

not to be one of them. I didn’t want to be some sort of ronin, some sort

of Wing Chun heretic.

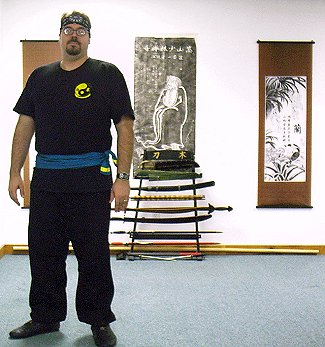

Towards the end of my Wing Chun

training, with my blue sash.

I grappled with my decision for a long time. I started showing up to

class less and less often. There were days when I did go, though, that I

tried to believe. I tried very hard to be the student I thought my

Sifu wanted me to be, hurting myself by refusing to quit when I went beyond my

physical limits. One evening I came home so bruised and wracked with pain

that I couldn’t go to class for the rest of the week. During one class I

overdid it so much that I stood there in a daze while working with another

student until he clocked me in the face with an elbow while I just watched.

These problems were nobody’s fault but my own because I was ignoring my own

safety in my need to prove something to myself. I could have trained in a

less… hysterical, more consistent fashion and I certainly had no problem

meeting the physical demands of the training on a day to day basis. The

problem was that I just wasn’t having fun. I was utterly miserable and hated my training. Finally, I admitted it to

myself.

Ultimately, I asked myself this question: If someone wrote to me in my

capacity as publisher of The Martialist which happens often and told

me this story, what would I tell that person? If I received an e-mail from

an unhappy student whose tale mirrored my own, what would be my advice?

As luck would have it, during the latter portion of my time at SWCA I started

training in Liu Seong Gung Fu, an Indonesian system. I enjoyed the

lessons. I liked the instructor. I looked forward to going to

class. I realized, as I contemplated my dilemma, that the decision was

clear. I did just what I would have told someone else to do in that

situation: I stopped training in something I did not enjoy and devoted my

time to things I did and do enjoy.

Was my problem with Wing Chun itself? No. I liked the system and

I might even train in it again elsewhere, though that’s not likely. Was my

problem with the school or the teachers? No. I liked the people

there and never had a problem with the staff of the school. Was my problem

me? It was, but only in that I had to figure out what I wanted

and then decide if this particular school could indeed provide me with that.

Has the sun set completely on my time with Wing

Chun? Probably.

It wasn’t an easy decision, but it was a necessary one for each of

us must, as students, maintain an active mind. We must examine our

training critically at all times, both with regard to its benefits and

with regard to our desires. At all times in your training, ask

yourself: is this right for me? Is it furthering my goals?

Am I enjoying it?

Life is too short to spend your time doing something you hate. No

matter how well-motivated you are, such self-imposed misery will eventually

grind you down. Instead, take the hard decisions. Make the necessary

choices. Search, and keep searching, for the training that best suits you

training that gives you the skills you want and need, but which is enjoyable

and in keeping with your sensibilities as a student and as a martial consumer.

You are more than a groveling supplicant whose teachers are doing him the

favor, granting him the privilege, of allowing him to spend his money at their

feet in exchange for their wisdom. You are a sovereign adult who is

entering into a mutual agreement with your instructor, to mutual benefit.

If you’re not receiving that benefit, it’s

time to move on.