You really shouldn’t fight force with force.

I can hear the incredulous gasps now. “What?” some readers may be asking. “Has The Martialist adopted the self-destructive philosophy of pacifism?”

Rest easy, friends. While the initial reaction to such a statement is, quite rightly, scorn and skepticism, I don’t mean that assertion the way it might sound.

Refusing to fight force with force means recognizing a simple concept. In a contest of muscle, the stronger contestant will always win. I don’t know about you, but even as a big guy I know there will always be people who are bigger. I don’t want to try to muscle my way through larger, stronger attackers if there is a better way. To look at it from the perspective of this publication, a force-on-force contest of strength is a “fair fight.” I don’t want a fair fight. I want an unfair advantage. I want to win as pragmatically as possible.

Bruce Lee exhorted us to “be like water.” Water seeks the path of least resistance. Its force is dissipated when it strikes a stronger barrier, but its current is devastating as it seeks its way around.

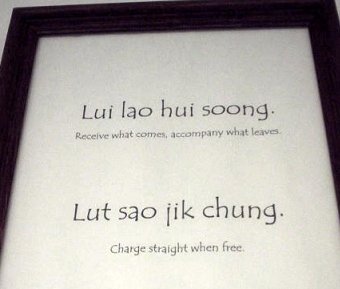

A Chinese saying we were taught in my old Wing Chun kwoon summed up this concept in more detail: Lui lao hui soong. Lut sao jik chung. Translated loosely, this means, “Receive what comes, accompany what leaves. Charge straight when free.” These simple words embody the fighting principles of the close-combative art of Wing Chun. They are sound principles for any fighter. We’ll examine each component in turn.

“Receive what comes” means absorbing or slipping a blow rather than trying to muscle through it, taking its brunt without flexibility. If I try to block a swing with a baseball bat using a simple Karate upper block, I’ve tried to fight force with force — and I’m going to lose the contest. To “receive what comes,” by contrast, the defender would turn with the blow, guiding the weapon past the body rather than crashing against it.

To “accompany what leaves,” then, is to exert control or guidance over attacks thus slipped or evade. If I give my baseball bat-wielding attacker a vicious pull after avoiding his strike, helping him on his way to an abrupt meeting with the floor, I have “accompanied” him in “leaving” me.

“To charge straight when free” is the essence of any direct, effective fighting art. If the opponent leaves an opening, you take it, blasting through holes in his guard and overwhelming him.

To use the baseball bat example again, let’s say I was slow in dealing with the initial attack, which is why my attacker was able to perform a swing. Let’s say I stupidly allow him to stand and attack again. When he gets to his feet and then cocks his bat back, he has opened his center. There is no barrier between him and me. I “charge straight,” bringing the fight to him, jamming his bat arm and counterattacking ruthlessly.

This extended example is a specific application of broad trinity of principles. These three concepts can be applied to any situation. Refusing to fight force with force is not a passive refusal to use force. Rather, it is the recognition that the collision of an immovable object with an unstoppable force produces only a standoff. Refusing to fight fairly means circumventing your attacker’s strongest attacks and defenses to exploit both your own strengths and his weaknesses.

To receive what comes is to evade an attack you cannot meet directly. To accompany what leaves is to redirect an attacker’s energy, using physics against your foe. To charge straight when free is to attack when and where your opponent is vulnerable, preempting his attack whenever possible.

Apply these principles to personal combat and you will increase your odds of success.